February 2026

March 2018

“Water, water everywhere, but not a drop to drink”. The line made famous by poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge provides a good description of the world’s water supply situation. And his words have perhaps never been more relevant than today.

Around 70 percent of our planet’s surface is covered by sea water. Estimates vary, but the oceans contain about 1.5 quintillion (1,500,000,000,000,000,000) tons of the life-giving liquid – and there’s a lot more circulating in the air, in the ground and in our bodies. So you might imagine that providing sufficient water for the world’s population to survive and prosper isn’t much of a challenge.

The problem is, however, that some 98 percent of the planet’s water is salty. And of the remaining fresh water, only a relatively small proportion is readily available to use as drinking water or to supply other consumer, production or agricultural needs (lakes and rivers, for example, contain only around 0.035 percent of the planet's total water supply). To make matters worse, the pressures of climate change, population growth and increasing affluence are placing a heavy, growing burden on fresh water supplies.

More and more, therefore, the world’s local authorities, and industrial or agricultural producers are turning to sea water as a source. But going from salty to fresh water isn’t quite that easy.

Desalination in focus

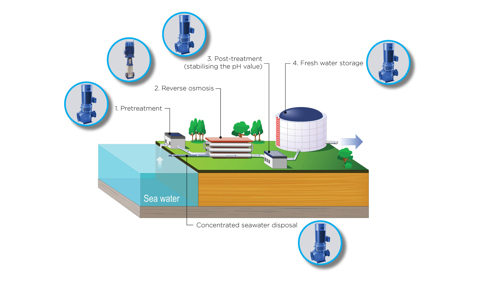

Desalination is the process of producing drinking water and service water from seawater. It’s a process that doesn’t vary much around the world: Sea water is pumped from coastal inlet pipes, processed under high pressure through filters, then pumped onward, typically to reservoirs dotted around the landscape.

Torben Harlev Mai is an Application Manager at Denmark-based pump system manufacturer DESMI. DESMI provides industrial pumps for a wide variety of applications including desalination, with different models and capacities for water purification systems or reverse osmosis (RO) treatment. With more than 100 years in the field, DESMI centrifugal pumps have carved out a reputation around the world for high reliability, low maintenance costs and low NPSH (net positive suction head) values. The powerful DESMI DSL double suction pump, for example, is ideally suited to seawater intake – and the company has a full range of pumps for brine, recirculation, backwash and transfer.

Efficiency first

“It’s absolutely crucial to use highly efficient pumps at each stage of the desalination process,” says Torben. “That’s because it is very expensive to make water in this way. By comparison, pumping up and purifying groundwater uses around 2.7kWh of electricity per cubic meter. But for desalination, it’s 5 to 6 kWh – or double the energy consumption. And that’s not good for operating costs or for the environment.”

Efficiency isn’t the only parameter, however. The salt content of sea water and its varying temperatures around the earth aren’t exactly friendly toward man-made equipment. But supplying pump solutions to the maritime industry as its primary business area, DESMI is an expert at dealing with such challenges.

“You simply can’t afford to have downtime in an offshore environment,” explains Torben. “Particularly if we’re talking about a pumping system for cooling a ship’s engines. And it’s the same basic pump that we adapt to work dependably in a desalination plant.”

In fact, most of DESMI’s pumps and related equipment is built to handle even harsher conditions, transferring, for example, heated bitumen or highly abrasive chemicals. For sea water being transferred at temperatures below 15 °C (59 °F), cast iron is used for the pump’s casing. From 15 to 40°C (59-104 °F), nickel alloy is needed. And for pumping sea water at 40 to 60°C (104 to 122 °F) in the Middle East, nickel alloy bronze or super duplex is demanded.

DESMI’s expertise is especially demanded at the higher end of pump dependability, which explains why the Middle East is an important and fast-growing market for its solutions.

Research and development

The Danish-based manufacturer, whose subsidiaries and distribution network stretch around the globe, is big on research and development, too. So, while it offers a wide range of standard pumps as a starting point, a growing number of orders are customised to meet specific customer requests.

At the same time, DESMI welcomes new ideas in the desalination field that can help to alleviate approaching water shortages. And, in recent years, plenty of ideas have surfaced – some short-lived, others holding the promise of better technology in the not-too-distant future.

“A lot of smaller companies and university research teams are working on other approaches to desalination,” says Torben. “One idea, called ‘vapor compression desalination’, involves spraying salt water at high pressure into a heated, voluminous space, then collecting the vapor. This delivers high-quality potable water, but not in the quantities required to supply the needs of even a smaller city. And this is the essential problem with practically all alternatives to traditional desalination techniques: insufficient flow capacity.”

DESMI pump systems are available to power new solutions, and the company monitors or participates in attempts to arrive at workable, high-flow approaches. But for now, local authorities trying to keep up with fresh water supply requirements must focus on well-proven, high-capacity technologies.

Averting disaster

Torben is well aware of the issues DESMI is helping to solve: “Fresh, clean water supply is an extreme challenge for the world. This has, of course, been known for quite some time, but the situation in Cape Town, South Africa, in the beginning of 2018 shows how big a problem the populations of many different regions of the world may be facing. Answering this challenge, in part, is up to companies like our own that can supply efficient, reliable pumps as key components of the many new desalination plants that need to be planned and commissioned with as little delay as possible.”

For now, DESMI is best able to help by providing its solutions, along with information and advice on pump choices for such plants, and by maintaining the high reliability its pumps are known for – because unscheduled downtime, when it comes to providing fresh water to large populations, could cost lives.

“Our office in Dubai is helping the engineers who advise Middle-Eastern utilities and manufacturing companies on water desalination issues to determine the best setup for new investments – discussing pump applications, types, capacities and servicing plans to keep the flow strong and plentiful. The same goes for our offices in China, Singapore, Africa, Denmark etc. Wherever we can help with our competences within desalination – we take part”.

“In 1995, World Bank vice president Ismail Serageldin declared that the wars of the next century will be about water" says Torben. “Hopefully, that’s not the case, of course. But if we can do anything more to change the future for the better, we will.”

February 2026

November 2025

October 2025

October 2025